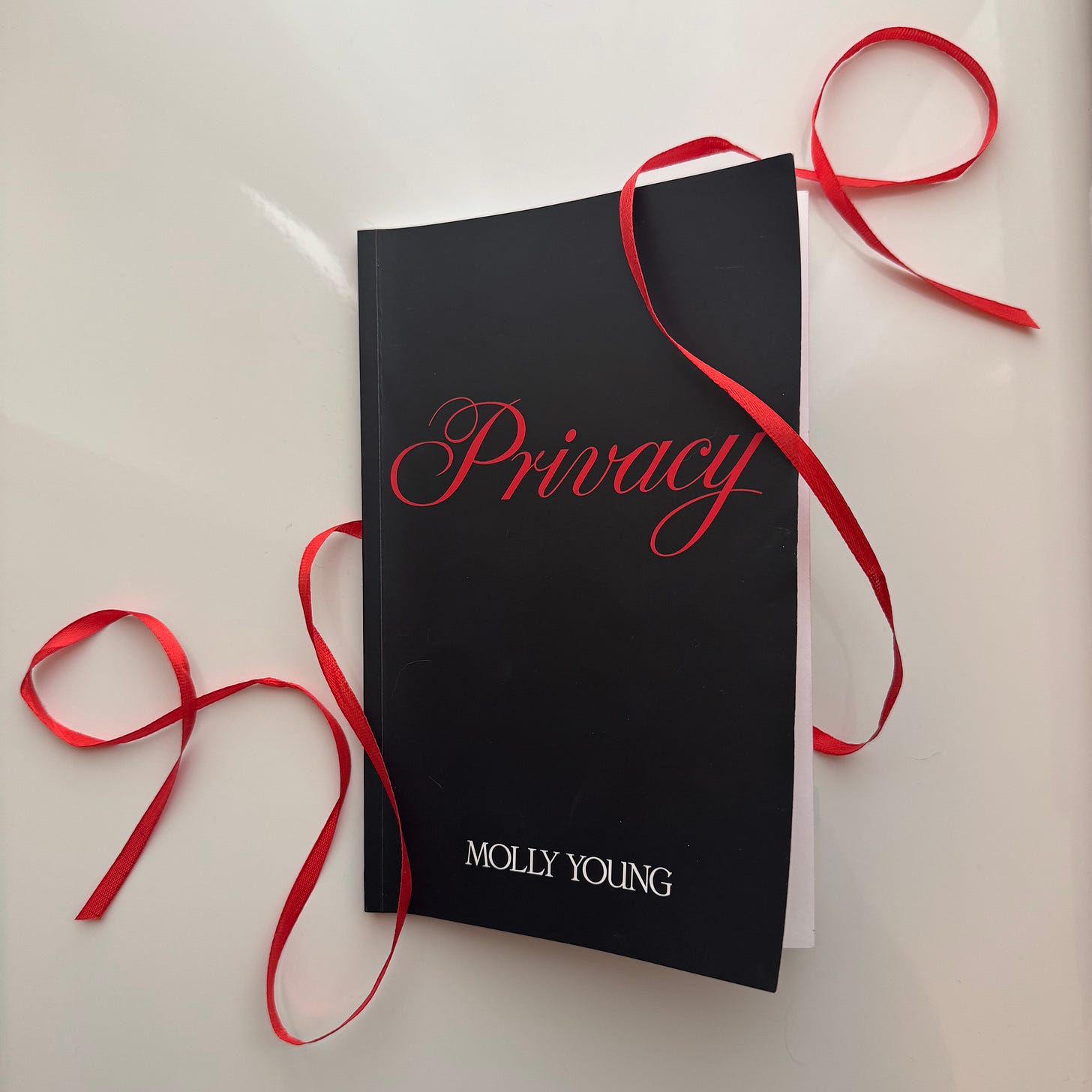

Privacy. Molly Young. Young Blanks / Titular Press, 2025.1

“Something I hadn’t considered: the best-case scenario is to extrude a healthy baby and then spend the rest of your life worrying that it will die.”

“Extrude” is the correct verb. As with everything Young writes, this zine is a tightly woven net of such perfect phrasings. On sleeping position: “After 20 weeks you’re supposed to huddle on your side at night like a Pompeii casualty.” On chronological destabilization: “I’ve fully ceded mastery over this substance called time, which is yet another way in which pregnancy mimics illness: a sense of calm really does descend once you’re dragged from a sea of choices into the straits of requirement.” On the beauty of the world once the child has been extruded: “liquid sun shoots through the windows as if by God’s own firehose.”

The title itself, of course, is perfect, too. Pregnancy is a brute displacement into a state of zero privacy. There is another person inside of you, and so you are never alone. The activities for which privacy could previously be assumed—peeing, sleeping—cause this new person to register their displeasure.

This new person’s company is mysterious. Communication with it is, in a sense, a conversation between strangers. But there is no one whose word I have ever desired more than that of my daughter when she was not yet born. I was constantly staring at a printout from the 3D ultrasound and trying to extrapolate information about her personality. There was a strong physical desire to hold her in my arms.

Rachel Cusk writes in A Life’s Work that when her daughter was lifted out of her sliced-open abdomen, “I recognized her at once from the scan.” I yearned for this experience but was too dazed, when a child was placed on my chest, for any kind of recognition, any kind of cognition at all. However, I recognize the kick she makes now when she reclines on my lap as the kick she made in the womb. It is the same foot, with the same force, at the same tempo.

*

My primary mode of relating to the world during pregnancy was incredulity. What I wanted to ask everyone was: are you fucking kidding me?

Other people who had been pregnant: this is what it’s like? You were this uncomfortable, and this psychedelically sensitive to time?

Children, adults, strangers, anyone: this is how you entered the world?

But most of all, ob/gyns: this is all you know about the experience of pregnancy? You went to four years of medical school and four years of residency in obstetrics and gynecology and perhaps several additional years in a specialized fellowship, you may even have gone through pregnancy yourself, and yet your only response to questions about symptoms experienced during pregnancy is a shrug?

How gratifying, and also infuriating, to read that Young got the same response. “A shrug,” she writes, “is the signature gesture of the ob/gyn experience.” When she asks hers about a symptom—was it common? Why was it happening?—the ob/gyn tosses back a single word from halfway out the door: “Hormones.”

Ob/gyns consider this an adequate answer to most questions about pregnancy that begin with the word “Why.” Why, for instance, do I have so much extra blood? Why are taste buds constantly bursting on my tongue? As a pregnant person, I was intensely curious about the answer to these questions, and as a formerly pregnant person, I remain curious. Why do the doctors who have chosen to specialize in the condition not share this curiosity?

The most significant whys involve the variability of suffering. For instance, I did not vomit even once during pregnancy, but I was nauseated one hundred percent of the time. Nobody knows why some people vomit and some do not, why some are nauseated and some are so extremely nauseated that they must be medicated or hospitalized, why some are nauseated and some are not, why nausea begins and ceases, or when such a thing might happen.

“Scientists have sequenced the genome,” Young writes, “but pregnancy-vomiting eludes understanding.”

*

The one pregnancy book I permitted myself to read was Your Pregnancy and Childbirth, a textbook-sized tome published by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Surely, I thought, this book will involve some explanation, even if reductive and dumbed down, of the mechanics of pregnancy. (Also, my therapist had forbidden me from scrolling Reddit.) But no. “The emotions you are feeling—happy or sad—are normal,” chirps the book. “Remember that worrying too much about how often your baby moves is not good for you or the baby.”

Most amusingly: “Researchers are still learning why pregnancy causes memory changes. In the meantime, don’t be worried. It may help to keep lists of things to do at work or home.”

Don’t worry about it, sweetie!

In the meantime, a PubMed search for pregnancy and memory returns abstracts like this: “Converging evidence indicates that pregnant women report experiencing problems with memory, but the results of studies using objective measures are ambiguous.”

The ob/gyn who delivered me told me, as I sat in the triage room having just been informed that I was zero centimeters dilated despite experiencing what I thought was unsurvivable pain, that she couldn’t tell me when I might be dilated enough to admit. “Any prediction you make about childbirth will be proven wrong,” she informed me cheerily, clapping her hands together once. Then she left.

*

“Who am I? is a question that never occurred to me until recently, when it began to occur constantly. It is often followed by What was I? and Will I ever be that again?”

I first thought that questions during early pregnancy were about not being so much as having. Will I ever again have the ability to recall a line from a book without retrieving the actual book from the shelf? Will I ever again have the unhealthy feeling of lightness that comes from starving oneself voluntarily? But these are, of course, questions of being, too. I had a conception of myself as the kind of person who held strings of words inside her head. I believed the residual effects of disordered eating were constitutional in me. To encounter the phrase “personal pronoun anorexia,” referring to Cusk’s motherhood memoir, was a small shock.

I believed I was a mind that could triumph over hunger. I did not believe I was a body. Various women told me that pregnancy had “healed” their relationships with food. I found the opposite to be true. I resented feeling hungry and made it everyone else’s problem, namely my husband’s, because he happened to be present.

Young writes that she ate a sandwich of “American cheese and mayo on white bread” every few hours during early pregnancy. That she hated this sandwich, which tasted like “air that has gone bad,” and yet ate it anyway. I don’t know if the desire for hyperprocessed grains and dairy is a known effect of hormones, or a coincidence, or nothing, but I felt it too. I ate a microwavable bowl of Annie’s mac and cheese every day. The waste was part of its appeal; I was feeling generally spiteful, irritable, and childish. Once the baby was out, the second bowl in a pack of two sat in my cabinet for months until finally, disgusted, I threw it in the trash.

*

Pregnancy and anorexia are both concerned with eating time. They are teleological states, experiences to be gotten through. This is clearer in pregnancy, which has several possible outcomes but a definitive point by which at least one such outcome will occur; you will not still be pregnant after two years, unless you are an elephant. The outcome, the telos, is trickier in anorexia. Really it is death. But the practicing anorexic believes that it is something slipperier and nonexistent, a state of perfect lightness.

In the preface to this zine, Young notes that there are “many literary books—fiction and nonfiction—about birth and motherhood, but strikingly few about pregnancy.” (There is a tantalizing footnote symbol with no corresponding footnote!) This cannot be simply the fact of pregnancy’s association with female experience, because birth and motherhood share that association. It can’t be the similarities between pregnancy and illness, because illness memoirs abound, and they compel even those who have never been ill.

There is something sensual in illness that does not exist in pregnancy, despite the slantwise proximity of pregnancy to the erotic. One can luxuriate in feeling sick, however perversely, but not in pregnancy. Does this have to do with labor, with the imperative that a pregnant woman continue working until she literally bursts? (Or, if she is pregnant with a second or third child, that she continue caring for her other, external children as well?) Is this a peculiarly American state, or does it have to do with the legacy of Christianity, the veneration of the virgin? (Young has a good passage about an early-Christian analogy between Jesus’s supposed passage through Mary’s inviolate hymen and a ray of sunlight passing through a pane of glass.) Basically, is it about shame?

I think it is, but not only shame. I think it is about shame mixed with this peculiar attitude toward time. Anorexia, as an addiction, is shameful to recount, but the proportion of anorexia memoirs to substance-addiction memoirs does not correspond to the proportion of real-life sufferers. There is something more appealing about recounting that time you spilled a vial in your purse and then had to spend two hours tweezing individual damp flakes of ketamine out from the surrounding mixture of dirt and loose tobacco. At least there’s the possibility of humor. But recounting the increasingly small pieces into which you cut raw vegetables doused with zero-calorie condiments…it’s just boring; Alice Gregory was right. The addiction is to a lack.

*

There is “a violent climax” to this zine, just as there is always a violent climax to a birth experience. Something tears; someone is sawn open; someone dies. The superstition of the pregnancy experience requires covering over these inevitabilities with silence.

The operant false belief seems to be this: if we admit how psychologically and epistemologically destabilizing the experience of pregnancy is (truths debunked: I am one person; my death, the cessation of my consciousness, is literally inconceivable), we weight the scales in favor of death and not of life. We tempt fate; we invite tragedy to visit our children.

There is a conspiracy of silence around the experience for another reason: it is literally unbelievable. You will not believe how close you come to death.

Lucy Ives describes the proximity like this, paraphrasing Rachel Cusk (in Kudos this time): “Even during a ‘normal’ birth, you basically experience your own death.” Ives asks if the person she was before she became pregnant, the person who did not want to be pregnant or have children, has died. Basically yes, she decides. But language, here, does not suffice. She did not die. She experienced death’s closeness, its “availability.” Death moves in its own pattern of orbit, and the person giving birth draws near.

*

Young wonders if there are millions of unpublished pregnancy novels out there. If the compulsion to write about the experience exists, but produces only unpublishable work. Maybe there was an extended cut of Cusk’s book in which she dilated on the experience of dilating, and her editor was like: nah. The other possibility is that Cusk herself was not interested in recalling pregnancy, that she found it “boring” in retrospect. “Why would that happen?” Young asks. “I can’t think of another transformative experience that is fascinating to undergo but by all (lack of) evidence insufferably dull to remember.”

I do not find it dull. I purchased this zine the moment I learned of its existence and read it as soon as it arrived, skipping several meetings. I yearn for constructed, narrative accounts of pregnancy—anything more than the unsettling–reassuring anecdotal conversations with friends that occupied my pregnant days, or the shrug of the medical establishment.

When I was pregnant, I was constantly processing the experience via fiction. Characters in my novel turned up pregnant and refused to eat, watched their bodies grow and resolutely kept smoking cigarettes. Sometimes they articulated their desire to slice off their bellies and crawl away to die in secret like animals.

But then again, I did not think to narrativize the experience of pregnancy itself. These were incidental moments. It took another year and several rounds of revision, culminating in throwing out that novel entirely and writing a different one, to make pregnancy a constitutive part of the novel’s plot. Now it’s about pregnancy as a kind of demonic possession. Maybe this novel, too, will prove resistant to publication. We will see.

I said almost the exact same thing about OBGYNs lacking curiosity! I switched to midwives after the appointment that made me say that.

I am pregnant and instantly craved boxed mac and cheese when reading this paragraph 🤣🤣🤣